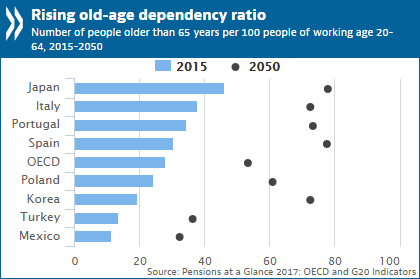

Pensions at a Glance 2017 says that public spending on pensions for the OECD as a whole has risen by about 1.5% of GDP since 2000. However, the pace of spending growth is projected to slow substantially.

At the same time, recent reforms will lower the incomes of many future pensioners. People will live longer and to ensure a decent pension would have to postpone the age of retirement.

“The world of work is changing fast”

The net replacement rate from mandatory pension schemes for full-career average-wage earners entering the labour market today is equal to 63% on average in OECD countries, ranging from 29% in the United Kingdom to 102% in Turkey. On average, replacement rates for low-income earners are 10 points higher and range from under 40% in Mexico and Poland, to more than 100% in Denmark, Israel and the Netherlands.

Over the past two years, one-third of OECD countries changed contribution levels, another third modified benefit levels for all or some retirees and three countries legislated new measures to increase the statutory retirement age. Under legislation currently in place, by 2060 the normal retirement age will increase in roughly half of the OECD countries, by 1.5 years for men and 2.1 years for women on average, reaching just under 66 years. The future retirement age will range from 60 years in Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey to 74 in Denmark, according to the latest estimations.

Over the past two years, one-third of OECD countries changed contribution levels, another third modified benefit levels for all or some retirees and three countries legislated new measures to increase the statutory retirement age. Under legislation currently in place, by 2060 the normal retirement age will increase in roughly half of the OECD countries, by 1.5 years for men and 2.1 years for women on average, reaching just under 66 years. The future retirement age will range from 60 years in Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey to 74 in Denmark, according to the latest estimations.

The projected increase in retirement ages will be exceeded, however, by expected advances in longevity, meaning that the time people spend in retirement will increase relative to people’s working lives. Employment at older ages will need to increase further to ensure adequate pensions for many people, according to the report.

Pensions at a Glance 2017 also looks at ways countries can meet the growing calls for more flexible retirement options

Rigidly set retirement ages might not be beneficial for society as a whole. Currently, only around 10% of Europeans aged 60-69 combine work and pensions. Of those that do work beyond the age of 65, half work part-time — a share that has been stable since the 1990s. Several countries including Australia, the Czech Republic, France and the Netherlands allow for early partial-retirement schemes.

Obstacles to combining work and pensions after the official retirement age exist, for example through earnings limits in Australia, Denmark, Greece, Israel, Japan, Korea and Spain. Barriers to continuing to work beyond the retirement age also exist outside the pension system, especially through age discrimination from employers or in cultural acceptance of part-time work.

Obstacles to combining work and pensions after the official retirement age exist, for example through earnings limits in Australia, Denmark, Greece, Israel, Japan, Korea and Spain. Barriers to continuing to work beyond the retirement age also exist outside the pension system, especially through age discrimination from employers or in cultural acceptance of part-time work.

Overall, for people with full careers, retirement is more flexible around the retirement age in Chile, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Italy, Mexico, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Sweden.

Policy makers need to ensure that postponing retirement should be sufficiently rewarding while not overly penalising people who retire a few years before the normal retirement age. In Estonia, Iceland, Japan, Korea and Portugal, the financial incentives to continue working after the retirement age are large but costly for pension providers. Flexibility should be conditional on ensuring the financial balance of the pension system, with pension benefits actuarially adjusted in line with the flexible age of retirement.

Published by the Editorial Staff on